Graphic Communication

|

Cynthia Ramsay, in her latest book Hawaii's Hidden Treasures (1993), notes that many tourists are drawn to the islands by the adventure of arduous hikes that take them to hidden valleys, wind through dense tropical rain forests, over volcanic landscapes, and onto hidden sand beaches lapped by azure waters. Many of these experiences would be out of the range of individuals with disabilities were it not for the helicopter industry.

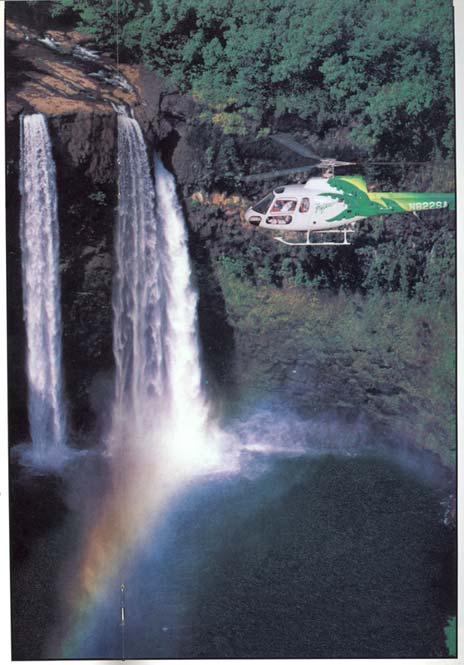

Since the 1980s the air tour industry in Hawaii has grown rapidly. By 1991 there were 101,000 helicopter air tour flights carrying about 400,000 sightseers over the islands. Some of the air tour operators advertise dramatic flights "close enough to waterfalls to feel the cooling mist." Other advertising brochures describe entry into one-way canyons while another invites tourists to "fly into the heart and heat of an active volcano" (Federal Register, September 26, 1994).

Given vacationers' willingness to take helicopter air tours and with opportunities for expanded air tour services, the U.S. Congress required the National Park Service (NPS) to investigate effects of aircraft overflights on the National Parks {Public Law 100-91, The National Parks Oveiflights Act of 1987).

In a recent Report to Congress (September 12, 1994) pursuant to PL

100-91, the NPS identified three main reasons why aircraft flying low over

not only Hawaii's parks, but the Grand Canyon and other national parks as well,

present the NPS with a very different and unusual set of problems. First, the natural

quiet found in many national parks has long been regarded as a park resource-solitude

and tranquility are often the very fabric of many national park experiences.

Back country visitors, people on oar-powered river trips, and those who take

short hikes away from their cars consistently show greater sensitivity to the

sound of helicopter overflights than do visitors who stop at easily accessible

overlooks. "Helicopter flights have intruded on our privacy and peaceful enjoyment

while hiking through our "natural preserve areas," complained Douglas Petroni,

one of dozens who filed comments with Federal agencies in the past months (The

NY Times, July 10, 1994).

Second, wildlife is also a treasured park natural resource and is impacted by helicopter overflights. In general, low altitude aircraft overflights near wild animals may cause physiological and/or behavioral responses that in turn reduce the wildlife's fitness or ability to raise young.

Third, a sizable number of visitors take advantage of the opportunity to view the parks' natural resources by air. Air tour passengers typically indicate immense enjoyment from their tour experiences and believe it increases their appreciation of the park. Health and physical disabilities have been identified as two of the main reasons people take such tours.

Passengers, however, are generally not aware of the risks involved with low flying air touts. In the past three years, 24 people have been killed on flights in Hawaii, most recently when a helicopter crashed last July. That accident was the 11th crash in just six months in which people were killed or injured while touring Hawaii by air (The NY Times, November 6, 1994). Due to this recent escalation of fatal accidents in Hawaii, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has implemented Special Federal Aviation Regulation (SFAR) # 71 to address this unique problem (Federal Register, September 26, 1994).

At FAA public meetings in Hawaii last year, a number of individuals commented that they witnessed helicopters flying dangerously low over scenic areas. The air tour accidents in Hawaii have often been attributed to insufficient time for pilots to locate suitable landing areas after engine power loss. The SFAR requires that air tour operations not be conducted below an altitude of 1,500 ft. Bob DeCamp, President of the Hawaii Helicopter Operators Association, however, notes that the" 1 ,500 ft minimum flight altitude requirement is not designed for safety, but is in fact intended to address helicopter noise."

Many helicopter passengers are elderly, disabled, and/or children who do not have the physical prowess or stamina to hike to remote areas. In the months ahead, if the SFAR ruling effectively imperils Hawaii's helicopter air tour industry, would such action infringe upon the rights of those with disabilities? Which is more important-preserving nature or maintaining the rights of individuals with disabilities and others who might not otherwise experience some of the most breathtaking scenery on earth? Is there an alternative to either extreme?