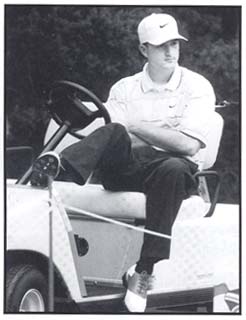

AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS

Casey Martin at the Nike Greater Austin

Open, March 7, 1998

|

Casey Martin, a 24-year-old golfer with a circulatory disorder in his right leg, recently initiated a national debate on the nature of professional athletic competition. As noted by legal scholars, Casey Martin vs the PGA Tour Inc. is the first case in which a professional athlete invoked the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). He sought a change in the PGA Tour's rules to play the game using a golf cart.

Martin has a condition called Kippel-Trenauncy-Weber syndrome, a rare congenital circulatory disorder that hinders his ability to walk. Blood tends to pool in the lower right leg-which is half the size of his left leg-causing swelling and chronic pain. With the use of two support stockings, extending from Martin's toes to his groin, sufficient pressure is developed to force blood back up his leg and thus reduce swelling. The atrophied leg has hemorrhaged so much playing golf the last five years that the tibia is at risk of fracturing. Much of the testimony in Martin's landmark civil suit revolved around a single issue: is walking the links important to golf competition? During the trial, arraignments were made that using a cart rather than one's legs would remove athleticism from the game.

National Public Radio (NPR) commentator Diana Nyad feels that granting this special exception undermines the competition. "...Imagine this scenario. The pros are playing an event in Scottsdale, Arizona. The desert sun pushes midday temperature to 100 degrees. On day four, Casey Martin is in the hunt for the lead or even a respectable place in the top 20, where the prize money for each position is significantly different. Would it really be fair to the rest of the players to go up against a man who has been protected by the shade of a cart and has only to muster enough energy to step out select a club, and take a swing, while the other players have been striding the hills in that heat for four days? Would that really be fair?" (Morning Edition, NPR, February 2,1998). Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, and Ken Venturi all testified for the PGA Tour during the trial, saying that fatigue can affect the game.

In rebuttal, Edward A. Eckenhoff, President of the National Rehabilitation Hospital in Washington, said there was clear evidence that a golfer with a physical disability expends more energy than a non-disabled golfer who walks. "There are studies that show that people who limp clearly burn more calories than an able-bodied golfer who walks" (The New York Times, February 12, 1998).

In a crowded Federal District courtroom in Eugene, Oregon, on February 11, 1998, Judge Thomas M. Coffin gave Casey Martin the right to use a golf cart during the Nike Tour-the minor league golf circuit. Coffin acknowledged the walking only rule is substantive but contended the PGA Tour failed to prove that waiving the rule for Martin would fundamentally alter competition. "The fatigue level from (Martin's) condition is easily greater than that of an able-bodied person walking the course" (USA Today, February 12, 1998).

The PGA Tour is planning to appeal Coffin's decision to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court in San Francisco. The merit of this initial decision, however, will be discussed for many years to come. To avoid other public relations nightmares, the PGA Tour and other sport organizations must actively discuss what constitutes appropriate accommodations for athletes with disabilities so that they may compete at an elite level with non-disabled athletes.

Sport officials must also realize that the ADA applies to all levels of athletic competition. Judge Coffin notes that "It's the same at the high school, college, pros, the rules are the rules, and it doesn't matter which entity has those rules" (The New York Times, February 12, 1998). The ultimate issue is whether the governing bodies of sport will defer each case of claimed disability to the courts or will they demonstrate the resolve to provide athletes like Martin the opportunity to compete with accommodations but with no unfair advantage.

The PGA Tour recently dropped the slogan, Anything's Possible. How unfortunate! The Nike Corporation, the multimillion-dollar sponsor of the Nike Tour, just signed Martin to an endorsement contract, making him the latest spokesman for their new slogan, I CAN (formerly, Just Do It). The irony of these slogans may have helped Martin's case, but they also magnify the complexities of the modern world of sport.