|

|

A Folha da Frontera

James Hayes-Bohanan,

Ph.D. |

|

|

A Folha da Frontera

James Hayes-Bohanan,

Ph.D. |

BackgroundEarly in 2002, Cara appeared at my office door, telling me that she had just learned of my interest and experience in the Amazon. She had long dreamed of going, and was hoping to find a way of going with me. For many years, my friends in Rondonia had been asking me to bring students. Given the vagaries of travel to the region, I was glad to have the prospect of taking just one student the first time.Not being sure where to begin, I started showing Cara slides from my previous trips. When we got to the slides showing a clearing that was bulldozed in 1996 and starting to grow back in 2000, we knew we had found her project. We originally hoped to travel in the summer of 2002, but did not succeed in getting funding. We went back to the proverbial drawing board, working with Dr. Kim Smith (a colleague with vast experience in tropical ecology), and Cara obtained a small grant from the Adrian Tinsley Program to help support a brief research trip during our 2003 Spring Break. Meanwhile, I was fortunate to obtain funding from the Center for the Advancement of Research and Teaching to support several trips -- including this one -- related to a textbook project. |

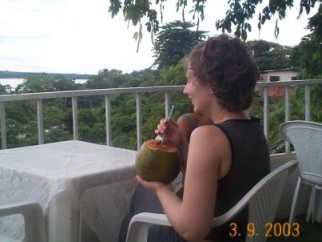

Cara overlooking the Rio Madeira and enjoying fresh coconut juice. Hiding behind her is Caliana, a new friend Cara met on the trip, who apparently is camera-shy. |

Cara was fortunate to stay with my friend, Graça Martins, who is a professor of English at UNIR, the Federal University of Rondônia. Graça is seated near the center of this photo on her back porch. Any number of Graça's friends and family and former students are likely to be around at meal time. She is a wonderful hostess and virtual campus mom. Sergio Rivero, seated at the left, is an economics professor who hosted me for part of this visit and provided access to many of the materials I needed for my research. |

|

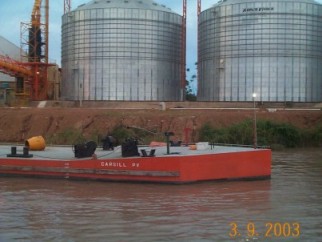

I took both of these photos during an outing on the Rio Madeira, and each

reveals an interesting reality about Porto Velho. The good ship Splendor

is used by the state government to provide social services to people

living in homes more easily accessed by river than by road. Such people,

known as caboclos or ribeirinhos, are and interesting part

of the part of the population; most are not considered indigenous, but

many have roots in the region that predate the waves of immigration that

followed settlement programs in the 1970s and 1980s. The second photo

shows that Rondonia is becoming ever more connected to international agribusiness

as Brazil pursues a policy of export-led growth. Although Brazil has substantial

industrial capacity, the pressure of international

debt payments result in a continuing emphasis on the export of raw

materials. In this case, vast amounts of soybeans from neighboring states

are being shipped through Porto Velho toward international markets, via the

Amazon River.

Because undergraduate research was the focus of our trip, it was

interesting that we spent the first day on campus listening to an undergraduate

research symposium at UNIR, the Federal University of Rondônia.

Each student presented results of research projects that had been funded

by grants; the program is much like the one that funded Cara's project.

Because undergraduate research was the focus of our trip, it was

interesting that we spent the first day on campus listening to an undergraduate

research symposium at UNIR, the Federal University of Rondônia.

Each student presented results of research projects that had been funded

by grants; the program is much like the one that funded Cara's project.

Many of the students were involved in ethnopharmacology research. This

is the very difficult but fascinating work of finding out what plants

are used for medicinally purposes by indigenous people, and then trying

to isolate the chemicals responsible for those curative properties. Because

indigenous cultures are disappearing even more quickly than the plants

in question, a global race is on to find this information.

This research is important but mired in controversy, and the students and

their professors are unable to publish most of it. The problem has to do

with intellectual property rights. The United States has so far refused to

sign an international convention on biodiversity, because it would protect

indigenous rights to information of this kind, at the expense of the

pharmaceutical companies that develop such information into marketable

drugs.

It was also good to see the availability of recycling facilities at the university campus. |

Porto Velho owes its existance to the ambitious railroad projects

of the early twentieth century. Lack of funds and the hot, humid climate

combine to accelerate the deterioration of the physical reminders of Rondônia's

railroading days. The EFMM Historical Society is leading an international

effort to save the historic rails, cars, engiines, and buildings. During

this trip, it was good to see some local interest in the project. The banner

reads, "Government and community united for the preservation of Rondonia's

history."

|

|

This map describes the layout of our study area.

The road along the northern boundary was created for the purpose of constructing

the gymnasium. Approximately three hectares (7.5 acres) were cleared prior

to construction. Most of this was allowed to grow back, leaving a grassy

area surrounding the gym itself. Fortunately for us, the construction also

included shower rooms, shown to the west of the gym. The work was hot and

sticky and buggy -- a nearby shower was an unexpected blessing! "Plot 1" is forest that grew back between 1996 and 2003. "Plot 2" is forest that was standing at the time of construction and has remained standing. Our transects were arrranged symmetrically in the two plots, as indicated in the northeastern quadrant of the map. |

|

I had spent a few hours in the rain forest during

each of my previous visits to Rondônia. Because I was traveling

with a biology student, however, this time I spent a significant amount

of time in the rain forest, and it was rewarding. LEFT: One of the first things I saw was this vine, whose leaves were so flush with the bark of the tree it was climbing that I thought at first that this was some very wierd tree! RIGHT: Cara's research design required us to start by finding old growth and new growth forest, and to establish transects of known length in each parcel. We sampled all of the understory (less than one meter) along a total of eight, ten-meter transects. The forest was thick, especially in the older growth, and progress was very slow, with many thorny trees, spider webs, and dense vines. The rain forest has multiple canopies, so that even these day-time photographs (with flash) appear quite dark. Because the rainy season had ended, we had only four to five rain storms each day! |

|

| These are two of the three dozen understory species

that Cara identified. The identifications are not considered official,

because we did not have the time to send specially-prepared samples to

a specialized botanical lab. The identifications were adequate for Cara's project, however, and she found a significant difference between the two plots, with the greatest ground-level diversity in the new growth. This met with our expectations, because of the greater light penetration to the surface in new growth. Had we had the time, equipment, and training to identify canopy tree species, we would have expected the opposite result. Reforested areas tend to exhibit far less diversity among trees than do old-growth areas. |

|

|

|

|

One of the saddest ironies of the tropical rain

forest is that the soils are among the poorest in the world. Rain forests

achieve remarkable productivity by capturing almost all nutrients above

ground. Any nutrients in the soil are leached out by the year-round, warm

rains. Many settlers and planners have been disappointed by these soils, having assumed that the abundant biomass was a sign of fertile soils. Typical agricultural settlements begin with the burning of biomass and mixing the ash into the soil. The result is remarkably fertile soil for the first year or possibly two. Following that, crops typically fail, and the land might eventually be used for bricks. |

I saw more wildlife on this one-week trip than I had in almost

four months of prior visits. In our field area on the edge of the UNIR

campus, we saw many blue

morpho butterflies, almost continuously flying along the dirt road

at the edge of our plots. I had seen just two before, and I never got tired

of seeing more of these large, brilliant insects.

I saw more wildlife on this one-week trip than I had in almost

four months of prior visits. In our field area on the edge of the UNIR

campus, we saw many blue

morpho butterflies, almost continuously flying along the dirt road

at the edge of our plots. I had seen just two before, and I never got tired

of seeing more of these large, brilliant insects.

Also on the access road, I saw an entire family of coatimundis,

a rare relative of the racoon that ranges from the Amazon to Arizona.

I had tried many times to see them in the Chiricahua Mountains to no avail, so

it was very exciting to see them in Rondonia. Unfortunately, Cara was

stuck in the forest with transect string, and could not get out into the

road in time to see these unusual creatures.

Finally, one day on the UNIR campus itself we saw this young man who had

just brought in a sloth he had found on the highway. Its hair was wet

and matted, and it was incredibly stiff and slow-moving. The biology professors

on hand assured us this was completely normal! They even suspected that

this individual might be pregnant. Perhaps UNIR has a new mascot!

|

|

Speaking of animal rescue, Cara was much enamored

of the stray cats in Porto Velho, of which there are plenty. I was glad

she did not try to bring these campus cats home on the plane; Bringing

home cachaça was enough of a challenge! This bird of paradise located at the edge of our study site was a pleasure to see each morning, and it marked the beginning of our transects in the new-growth plot. |

|

|

|

As in the rest of the world, proficiency with

computers is seen as an important way of getting ahead in Rondonia. Access

to computers is very uneven, but private schools throughout Porto Velho

provide computer training. The Federal University of Rondonia, of course,

is another center of computer technology. Because most places are not

air conditioned, computers tend to be clustered in those rooms that are,

such as my friend Sergio's office. Here, Graca checks her e-mail, which has become a very popular way for Brazilians to keep in touch not only within Brazil, but also with friends and family working abroad. Meanwhile, Sergio proofreads a PowerPoint presentation on my laptop while looking up related information for me on his. |

Lanchonettes - or lunch shops - are very popular in Brazil. Typical fare

includes sucos, which are juices or light shakes made from mostly tropical

fruits, and sanduiches of ham, egg, and/or cheese.

| This was the year of television appearances for

me. Earlier in the year, I had appeared on a local cable-access show in

Bridgewater, discussing the conservation work of the NRTB. Being a cable-access show, it has

aired many times, and people are always recognizing me from it. On our last day in Porto Velho, I had a similar opportunity, following a lecture I gave at UNIR. People in Rondonia are very interested in the research that I do, because so little research is done about anything but the most disastrous aspects of life in the region. Because I try to understand Rondonians on their own terms, my work has become somewhat popular. This is not to say that my own views are never challenged: this talk-show host embraced me at the end of a lively interview in which he asked some fairly tough questions. I love the decor: the shelves, books, and globe are painted on that wall! By the way, I was also interviewed for the newspaper! |

|

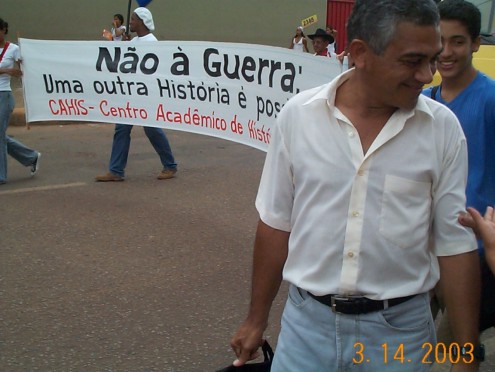

We were in Brazil just before the U.S. invaded

Iraq. Everyone asked me about this; nobody was a fan of Saddam Hussein,

but neither could anyone understand why the U.S. was attacking Iraq at that

time. The sign below reads "No to war: another history is possible." To

the right, my friend Graça's son holds a sign that says simply,

"Peace." On my Iraq web page, I try to explain

for U.S. citizens why so many people around the world were opposed to the

war.

[April 2004 addendum: this experience led me to create the Pax Mundo web site, which is dedicated to helping U.S. citizens understand how people around the world view our country.] |

|

|

|

| Early in our last evening in Rondonia, we had

the opportunity to visit the regular workout of a group of capoeira artists.

Capoeira originates

in Bahia, in the northeast of Brazil, but is popular throughout the country.

I think of it as a combination of martial arts and dance. |

|

|

At left is Gabriela (Gabi), the daughter

of my friend Gilmar. She has grown from a beard-pulling tot to a lovely

young lady. I told her my own daughter would love the Powerpuff Girls scarf! |

|

No trip to Brazil would be complete without some

airline difficulties. In this case, the trip to Porto Velho was fairly uneventful,

taking only 36 hours. Several wrinkles in the return trip stretched it

to 60 hours. First, the national airline Varig had five planes siezed for outstanding debts, so that our 2 a.m. flight from Porto Velho was canceled without our knowledge. We finally left around 11 a.m., on a flight from Porto Velho to Rio Branco to Goianas to São Paulo. Check an atlas to see exactly how circuitous a route this is, especially considering that the final destination is Boston! Our first attempt to land in Goianas was unsuccessful, with our landing aborted because of stormy weather -- while we were directly over the runway! That delay got us to São Paulo in time to get in line for our flight to Boston, but at the end of that line. We were bumped from the flight, which was a great dissappointment after almost 24 hours of travel. The next flight was a full day later. The airline put us in very nice rooms, however, and we wanted to take the hotel chef home with us! We were able to get some work done and be better rested for the remainder of our trip. |

|

The trip was a success for both Cara and me. I obtained

data that will be helfpul in writing our textbook, and I developed some

new contacts for other projects, including a second edition of our book

Olhares (see my main Rondonia Web page for more about this

project). With Cara's help I gained some much-needed direct experience

in the rain forest and gained some insights into how to organize future

trips with larger numbers of students. With colleagues in Bridgewater,

I am already working on plans for a more extended group trip to include

other parts of Brazil. At left, Cara and I are basking in the glory of her successful project during BSC's annual Undergraduate Research Symposium. |

For the 1996 dissertation trip, see Folha da Frontera - Volume I, No. 1

For the 2000 family trip, see Folha da Frontera - Volume II

To read about James' 2004 visit to Florianopolis and Rio de Janeiro, see

Folha da Frontera - Volume IV