Disturbance Ecology

Natural and anthropogenic disturbances can have extensive

and dramatic effects on the structure and function of ecosystems. Although the

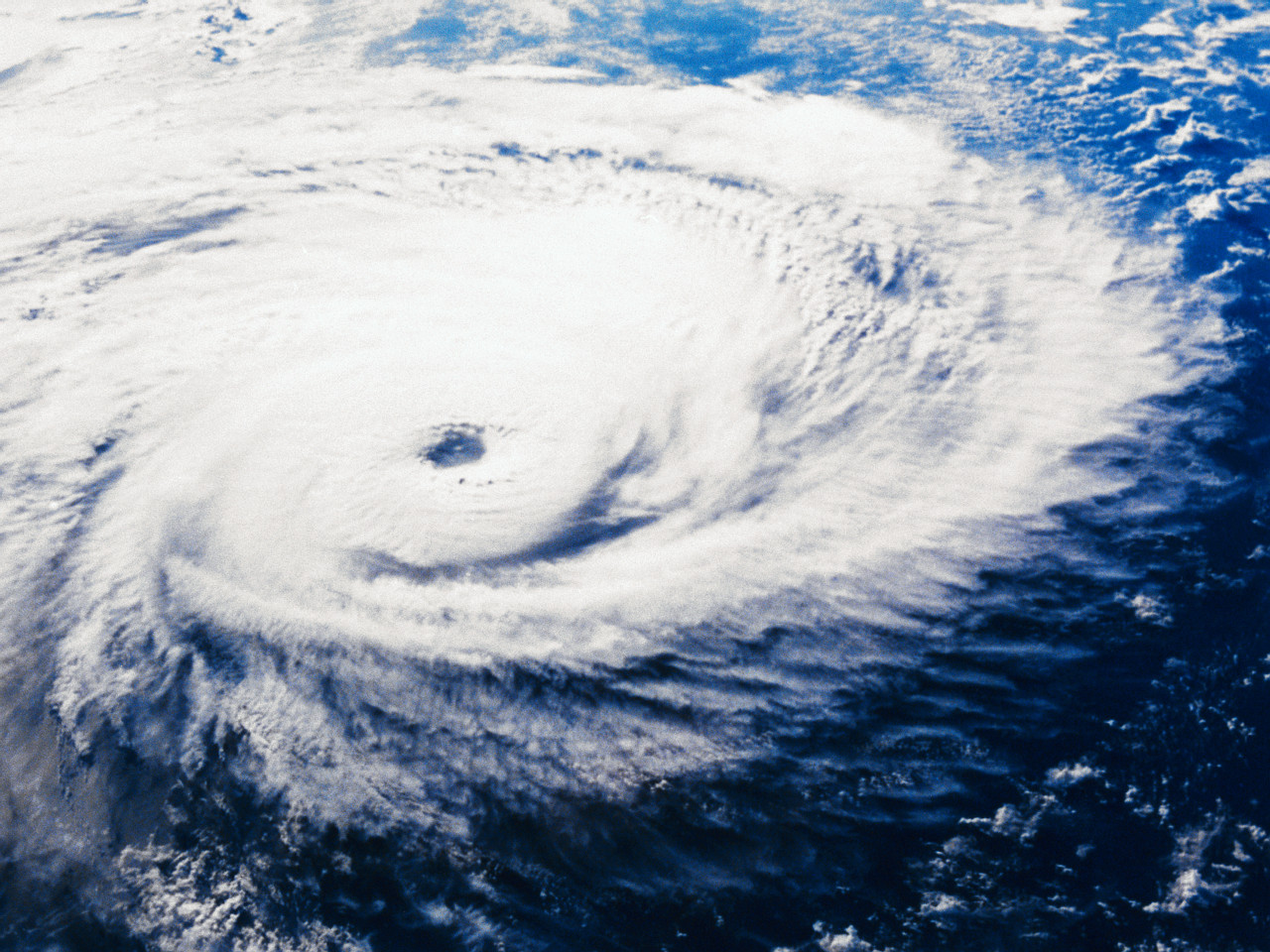

term “disturbance” conjures images of large-scale destruction (e.g., Hurricane

Katrina, Mt. Saint Helens), a wide variety of disturbances exists in most

ecosystems, and these events can range from very large, infrequent events, such

as hurricanes, wildfires, and volcanic eruptions, to frequent and localized

events like the digging of burrows by kangaroo rats. In fact, far from being catastrophic events for ecosystems, disturbances often contribute to the

maintenance of high biodiversity by preventing one species from driving its

competitors or prey to local extinction (Connell 1978).

catastrophic events for ecosystems, disturbances often contribute to the

maintenance of high biodiversity by preventing one species from driving its

competitors or prey to local extinction (Connell 1978).

The degree to which humans contribute to disturbance regimes should only increase as Earth’s human population continues to grow. Humans not only affect ecosystems directly, but also are altering natural disturbance regimes. For example, some projections suggest that increased global temperatures, largely driven by human activity, may increase the average intensity of hurricanes and tropical storms (Goldenberg et al. 2001, Webster et al. 2005). To truly understand the effects of disturbance on natural systems, we explicitly need to recognize the direct and indirect contributions of our own species.

I’m interested in both natural and anthropogenic sources of disturbance, as well as interactions between the two. As such, much of my recent work has involved long-term responses of populations or communities to disturbance. A few examples are illustrated below.

Literature Cited

Connell, J.H. 1978. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 199:1302-1310.

Goldenberg, S.B., C.V. Landsea, A.M. Mestas-Nuñez, and W.M. Gray. 2001. The recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity: causes and implications. Science 293:474-479.

Webster, P. J., G.J. Holland, J.A. Curry, and H.-R. Chang. 2005. Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. Science 309:1844-1846.

Recent and ongoing projects:

· Long-term effects of hurricanes on terrestrial gastropods

Large-scale natural disturbances,

such as hurricanes, can have profound effects on animal populations. Each

hurricane is unique in terms of extent (amount of area covered), intensity (wind

speed and amount of rainfall), trajectory, and the history of the disturbed

area. However, because of the logistical difficulties associated with studying

large-scale disturbances, most studies focus on a single hurricane and

extrapolate to other storms, implicitly assuming that the results will be

equivalent. Dr.

Michael Willig and I examined long-term patterns of population dynamics of

17 species of Puerto Rican gastropods to assess the degree to which the effects

of two hurricanes were comparable and generalizable among species. Responses of

populations were species-specific and exhibited several different types of

patterns. In addition, some species responded differently to the two different

storms, a result that suggests that differences in the intensity of storms or

their historical contexts may make it impossible to identify a universal

hurricane effect.

Bloch, C.P., and M.R. Willig. 2006. Context-dependence of long-term responses of terrestrial gastropod populations to large-scale disturbance. Journal of Tropical Ecology 22:111-122.

· Responses of Amazonian bat populations to human alteration of habitat

Although the Amazon basin in South America is home to an astonishing array of biodiversity, this diversity is increasingly imperiled by anthropogenic alteration of habitat (e.g., conversion of forest to fields suitable for agriculture). Alteration and fragmentation of forest can affect the population biology of species as well as the transmission dynamics of emerging infectious diseases. As part of a large, NIH-funded project examining the ecology of mosquito-borne diseases, I participated in a study that focused on how bat populations near the Peruvian city of Iquitos were affected by conversion of forest to farmland.

Willig, M.R., S.J. Presley, C.P. Bloch, C.L. Hice, S.P. Yanoviak, M.M. Díaz, L. Arias Chauca, and V. Pacheco. 2007. Phyllostomid bats of lowland Amazonia: effects of anthropogenic alteration of habitat on abundance. Biotropica 39:737-746.

· Distribution and abundance of the whipspider Phrynus longipes (Arachnida: Amblypygi): response to natural and anthropogenic disturbance

Little is known of the ecology of

this species. Laura Weiss and I quantified its habitat associations and

evaluated population-level response to natural and anthropogenic disturbance

history. Although canopy openness (a measure of recent hurricane da mage) had no

effect on population density, densities were highest at sites that had

experienced the least severe anthropogenic disturbance (selective logging, as

opposed to intensive logging or agriculture). This demonstrated that

human-induced changes in habitat may persistently affect densities many decades

after a site is abandoned and returned to a “natural” state.

mage) had no

effect on population density, densities were highest at sites that had

experienced the least severe anthropogenic disturbance (selective logging, as

opposed to intensive logging or agriculture). This demonstrated that

human-induced changes in habitat may persistently affect densities many decades

after a site is abandoned and returned to a “natural” state.

Bloch, C.P., and L. Weiss. 2002. Distribution and abundance of the whipspider Phrynus longipes (Arachnida: Amblypygi) in the Luquillo Experimental Forest, Puerto Rico: response to natural and anthropogenic disturbance. Caribbean Journal of Science 38:260-262.